Responding to Russia’s Attack on Ukraine

Overnight, Russia officially attacked Ukraine, and global markets are responding negatively. All of this comes on the heels of what has already been a challenging start to the new year, especially for US stocks. International stocks had fared better year-to-date, which was largely the result of a more hawkish US Federal Reserve relative to other global central banks. The thought was that with the Fed signaling a willingness to aggressively start hiking interest rates in order to fight stubbornly persistent inflation, there was a higher likelihood of over-tightening in the US, which would invert the yield curve, cause a recession, and ultimately end up doing nothing to ease supply chain problems that are producing much of the inflation. The Fed is trying to navigate a soft landing on what appears to be a gradually shrinking runway.

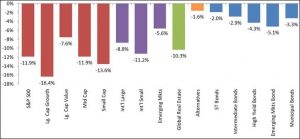

As we write on the morning of February 24th, here’s where global markets sit year-to-date:

Source: Morningstar Direct and Brand AMG

How did we get to the current situation between Russia and Ukraine?

Long story short, Russian civilization essentially began in what is today’s Ukraine, a fact to which Putin refers often when listing his reasons for wanting to bring Ukraine back under Russian control. Following the Bolshevik revolution in Russia in 1917, the Russian state of Ukraine declared its independence. Over the next few years, it found itself briefly occupied by Germany and Austria, and afterwards in a struggle between troops from Poland and Russia. In 1922, Ukraine became one of the original four republics of the USSR (along with Russia, Belarus, and the Transcaucasian Republic, which was later divided up into Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia).

Following the end of World War II, upon defeat of the Axis powers, the Allies (which included the USSR) created the United Nations in 1945 to foster international diplomacy and avoid a third world war by agreeing to outlaw wars of aggression. It also ushered in a new era defined by the rise of two new superpowers – the US and the Soviet Union. Much of Europe would be redrawn following the War, with Western European countries and Japan being rebuilt through the US Marshall Plan, and adopting more democratic and capitalist ideologies. Central and Eastern European countries would fall under the Soviet sphere of influence, and lean more communist. In 1949, NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) was created to better secure an alliance among the more democratic-leaning nations of the post-WWII environment.

Over the next several decades, the Cold War between the US and the USSR – the world’s two biggest superpowers – resulted in rising tensions and efforts to showcase which economic ideology was better (communism or capitalism). Economic stagnation in the USSR and other communist countries during the 1970s and 1980s led to the fall of the Berlin Wall, political conflict between many Soviet States, and ultimately the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 – an event which Vladimir Putin identified in 2005 as one of the greatest geopolitical disasters of the 20th century. After the fall of the USSR, Ukraine was again an independent state, but has been in a virtual tug of war between Russia and the West ever since. Eastern parts of the country which share a border (and dialectical similarities) with Russia are more sympathetic to Moscow, while the Western part of the country tends to yearn for greater alignment with the West, even hinting at a desire for membership to NATO.

So here we sit – a stalemate where Putin feels like Western influence in Ukraine since the collapse of the USSR is a threat to Russian security, conflicting with the US stance that Russia is aggressively interfering with a sovereign nation’s ability to choose democracy. Central to the idea of postwar Europe is that nobody should redraw European boundaries by force. So, Russia’s challenge isn’t only to a specific country (Ukraine) but to a whole world order. However, without Ukraine being a NATO country, NATO has no obligation to defend it militarily, and doing so risks an escalation from the Kremlin. This is why NATO members are instead trying to use sanctions to target the underpinnings of the Russian economy – Russian oligarchs, with the hope that they might increase pressure on Putin to reduce his ambitions.

Where the conflict ultimately shakes out is anybody’s guess. Invading a country is one thing, but actually occupying it is another. The Ukrainians are well-armed and have been trained by the West since 2014. That said, the Russian forces are much larger than Ukraine’s.

What does this mean for my portfolio?

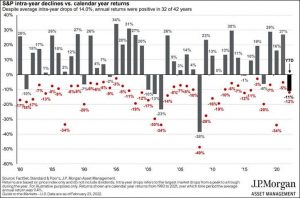

With the S&P 500 officially in “correction” territory (defined as a decline of 10% or more from its most recent peak), and other indices like the NASDAQ nearly in “bear market” territory (defined as a decline of 20% or more from its most recent peak), there are plenty of scary headlines today. The difficulty in times like these is keeping the proper context and not allowing fear to overcome potential positives like discipline. It can be difficult to remember – especially after what has seemed like one big long nearly 13-year bull-market – that stocks do experience volatility. In fact, over the last 42 years, the average intra-year decline is in the neighborhood of -14% (see below).

But staying invested, to experience what follows that decline, is most important – and one of the things that we can control as investors. Consider the following study from Dimensional Fund Advisors, which shows that the average annualized compound return of investing in the S&P 500 over the past 30 years has been +10.23%. For an investor who got out of the market and missed the single-biggest up day (which normally happen right after large down days), their return shrunk to +9.84%. Extending that analysis out to missing the 25-best days (again, which normally occur right after large down days), we find that the return is +4.88% – less than half of what it would have been if they would have stayed engaged in the market. This is a reminder that while stocks represent a risky asset class, it is one that only rewards investors who do not abandon them, and also illustrates how difficult (and costly) it is to time the markets.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that markets have seen international conflicts in the past. And while this one feels big, we should remember that Russia invaded Georgia in 2008 (which lasted for 12 days, but territories of which are still occupied by Russia) and Russia invaded and annexed Ukraine’s Crimea region in 2014 (which lasted just over one month). This may well be another swift territory grab followed by a long-term occupation, or it may be a more prolonged conflict. We don’t know which variety it will be, and as investors, this is something outside of our control.

What we must remember is that we should focus on the things we can control, such as staying diversified and using the portfolio management tools at our disposal to enhance future outcomes. These include such activities as rebalancing: selling bonds when they are higher (like today) in order to buy stocks when they are on sale (like today). Additional actions include tax-loss harvesting: capturing any losses that may be available in taxable accounts for use as a “tax asset” later (to offset any gains) when you file end of year 2022 taxes. We hope for a swift resolution to this conflict, and hope for a soft landing from the Fed. Regardless of whether we get either, we encourage investors to remain disciplined and focus on the tools that allow them to take advantage of periods of volatility. We’ve been through periods like this before, and will likely experience them again. Just know that we are right here for you and working hard to make the best of what we believe will be a temporary situation.